The Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) has prepared this report to draw the attention of international human rights organisations to the situation of secret detention centres of two security agencies, the Ministry of Intelligence and the Intelligence Organisation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), in Iranian Kurdistan.

The report briefly addresses the location of these secret detention centres and the detention conditions, interrogation, and torture that political prisoners face in these facilities.

Given the security situation in these detention centres and the obstacles to gathering information, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) has interviewed several activists who have, at various periods, been held in these detention centres.

Most of the information published in this report is derived from the in-person observations of these individuals.

The report examines the central detention centres of the Ministry of Intelligence and the Intelligence Organisation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in the cities of Orumiyeh, Sanandaj, and Kermanshah.

In the near future, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) will try to publish a report on two other security detention centres in Ilam.

Introduction

The Islamic Republic of Iran’s control over power was accompanied by political and military tensions in different parts of Iran. These tensions in Kurdistan reached their peak with the issuance of the jihad decree by Ayatollah Khomeini, the then leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, on 19 August 1979. Other attempts to reach an agreement at the negotiation table between the Kurdish political forces and the representatives of the Islamic Republic of Iran were unsuccessful. In May 1980, another round of armed clashes began between the two sides. These conflicts continued until the late 1980s. Under such circumstances, a wave of widespread arrests, tortures, executions, as well as plots to assassinate Kurdish political activists outside Iran were on the agenda of the security forces.

The Iranian revolution in 1978 gave hope to the Kurds as an ethnic minority towards a peaceful solution to the Kurdish question, but this hope did not last long. The establishment of the Islamic Republic, which in line with the previous government (Pahlavi dynasty), avoided focusing on resolving the ethnic issue, led to another round of policies of repression, intimidation, and atrocity in Iranian Kurdistan. Although these policies were not limited to Kurdistan and, in a gradual process, covered the whole of Iran, the repressions had higher intensity in Iranian Kurdistan from the very beginning of the formation of the central government. The beginning of the Iran-Iraq war in 1980 provided the necessary excuse for government forces to suppress their internal enemies more severely in the name of defending Iran’s borders. Under such circumstances, Kurdish political activists and many non-political civil groups fell victim to the repressive policies of the Islamic Republic.

After the end of the armed conflict between the armed forces of the Kurdish opposition parties and government forces in the late 1980s, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Ministry of Intelligence of the Islamic Republic of Iran continued their repressive activities in various parts of Iranian Kurdistan. In addition to suppressing any political and civil movement in the Kurdish region, the assassinations of members of Kurdish political parties opposing the Islamic Republic outside Iran, especially in Iraq and European countries, has been one of the most important activities of these two organisations. Assassinations of more than 100 cadres of these parties who lived in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq in the 1990s, as well as the assassinations of prominent leaders of the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (KDPI), such as Dr Abdul Rahman Ghassemlou in Vienna and Dr Sadegh Sharafkandi in Berlin, were among the most important terror acts committed by the assassination teams of these two institutions.

The two institutions continued to detain, torture, and prosecute Kurdish activists in similar ways but parallel with each other, using detention centres of the former National Organization for Security and Intelligence (SAVAK) and the ones they built anew. According to the research carried out by the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN), most of the director-generals of the intelligence ministry of the four provinces of West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and Ilam, were not Kurds but were from other parts of Iran. The only exception in recent years has been Mohammad Sadegh Motamedian, the director-general of the intelligence ministry in West Azerbaijan province. Motamedian, who is the current governor of South Khorasan province, is originally from Kermanshah. He worked in the past as the Director-General of the Ministry of Intelligence in West Azerbaijan province. He holds a master’s degree in management. Among others, he has held positions such as membership of the Sustainable Research Development Council of East and West of the country, the head of the Educational Policy Council of the Northwest of the country, and the deputy director of the intelligence ministry in Ilam and Kermanshah.

Today, the Ministry of Intelligence, the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC, the intelligence service of the Law Enforcement Force of the Islamic Republic of Iran (NAJA), and the Intelligence and Public Security Police (PAVA) each have separate detention centres in different cities of Kurdistan. The Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC has several secret detention centres in central cities of each of the provinces of West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah, and Ilam. The locations of some of these detention facilities have not yet been determined. The Ministry of Intelligence has a central detention centre in each of the provincial centres. Usually, all detainees from different areas of the province are transferred to these central detention centres for interrogation. The offices of the intelligence ministry in each county also have a small detention centre, which is used in emergencies, such as sudden street protests, strikes to protest against living conditions, and the like, which often lead to widespread detentions of citizens.

IRGC detention centres are primarily located in the bases of this military-security organisation. In some exceptional cases, several villas in residential areas are used as detention centres to interrogate foreign nationals and top-secret cases. Several activists detained in Orumiyeh and Kermanshah have reported their interrogation in some of these places, but so far, the locations of these top-secret detention centres have not been identified.

In 2009, after the transformation of the Intelligence Unit of the IRGC into the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC, this organisation began to build some new detention facilities. Some of these are located on the sites of the detention centres of the former SAVAK and have only been repaired and rebuilt in some cases. Several other detention centres have been built in a thoroughly modern style in military centres.

Regarding the quality of food in these detention centres, it should be said that before Mohammad Khatami’s government, each detention centre was supplied with food from the central prison of the province where it was located. However, since nearly the middle of the reform period, the food of the detention centres in all provinces, except for in the detention centre of the Ministry of Intelligence in Orumiyeh, is cooked and prepared either by the staff of the two security institutions or separately by a special chef.

Detention Centre of the Ministry of Intelligence in Orumiyeh

This security detention centre is located on Daneshkadeh Street in Orumiyeh, in the General Directorate of the Ministry of Intelligence building. The detention centre building has four corridors, and the corridors have 12, 10, 8, and 4 single and multiple-occupancy cells. These cells are 80 centimetres by 2 metres, 1.2 metres by 2 metres, 2 metres by 3 metres, and 3 metres by 4 metres. None of the cells has windows, and there are only openings in their ceilings for air ventilation.

In an interview with the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN), some individuals who have spent some time in this detention centre described it as one of the dirtiest and scariest detention centres of the Ministry of Intelligence in Iran. The bathrooms in each cell are extremely unsuitable and stinky, and dirty blankets are provided to detainees. Each cell has a bathroom separated from the detainee’s sleeping area by a one-meter-high open wall. In some multiple-occupancy cells, the bathroom and toilet are located in a separate room inside a larger cell.

The small space of the cells is sometimes allocated to several detainees. In this detention centre, unlike the ones in other provinces, the food given to the detainees is brought from Orumiyeh Central Prison, which is said to have very poor quality.

After transferring the detainee to this detention centre, the guards conduct a physical search and confiscate personal belongings of the detainees, including belts, shoes, cash, etc., and take the person into the cell in their own clothes. It also has a cell known as the “grave” cell, which is one and a half meters high and is 0.5 metres by 0.5 metres. In this cell, which is used only for torture, the person must stand for hours on foot. The walls of the interrogation rooms have a softcover, and the interrogations are carried out with blindfolded detainee facing the wall while the interrogator is behind him. In most cases, the detainee is beaten by the interrogator. According to former political prisoners, beatings are a common practice of torture by interrogators of the intelligence ministry. During interrogations, two torture team members stand next to the detainee’s chair, and if he does not answer the questions, the two men severely beat the detainee, such that in some cases, some of them faint as a result of the beatings. There is also a room specifically used for torture, in which the detainee is placed on a bed and flogged on the soles of his feet with cables and other tools. It is also common to use electric shock and hit sensitive parts of the body, such as the testicles.

A Kurdish civil rights activist, held in this security detention centre for several weeks, shared his experience with the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN). “I was immediately taken to a 2 metres by 80 centimetres cell which was nearly 3 meters high. It was a cell with an iron door and equipped with a CCTV camera with an open toilet controlled by the camera installed in the ceiling. Dry and lifeless cells with dry and dead granite stones. Everything there is prepared for the experience of gradual death. The colour of the stones depresses the soul and disturbs one’s inner world in a completely isolated place without the possibility of access to any media, not even a newspaper. I would get fresh air for 10 minutes every day in the yard. I could have been summoned for interrogation at any moment. There was no set time for interrogation. This detention centre is equipped with the latest torture technologies.”

The civil activist continued: “The interrogation room was 3 metres by 4 metres and was equipped with a CCTV camera. During the interrogation, one must sit with one’s back to the interrogator on a chair with an arm desk. The prison yard was triangular with an area of about 70 square metres. The basement of this detention centre is for torture. After being transferred to the torture area, several detainees were given electric shock using a special device installed in the wall. The severity of the pain caused by this device to the head and chest lasts for several days. It is also a full-blown psychological war when you are in a small multiple-occupancy cell with several people, with an open toilet and a camera over your head.”

Detention Centres of the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC in Orumiyeh

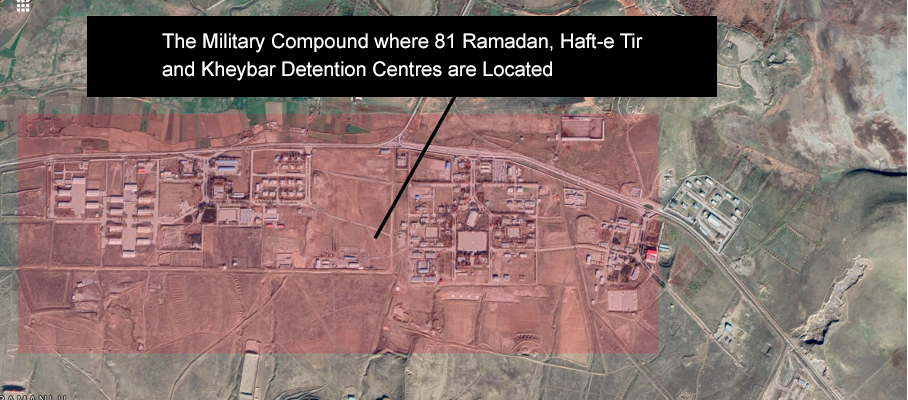

The Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC in West Azerbaijan province has several secret detention centres in and out of the city of Orumiyeh. As in other provinces, the main detention facilities of this security institution are located on military bases. One of this security-military institution’s three main detention centres is in the Al-Mahdi base known as the 81 Ramadan detention centre. The second is in Malek Ashtar base known as Haft-e Tir detention centre other is a recently-built detention centre called Kheybar. These three detention facilities are located 20 kilometres from the city of Orumiyeh, on the Orumiyeh-Tabriz road, in an entirely non-residential area, next to the Al-Mahdi and Malik Ashtar training camps, the north-western artillery centre, and the Hamzeh Sayyed al-Shohada camp of Orumiyeh.

According to some former detained activists, the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC was using the 81 Ramadan detention centre as its main detention centre for the past few years, but since a year ago, after the construction of Haft-e Tir and Kheybar detention centres, this security-military institution uses these two detention centres when necessary.

Accurate information is not available on these two new detention centres, but reports indicate that there are dozens of single and multiple-occupancy cells with a capacity of more than a few hundred people.

81 Ramadan Detention Centre Known as Al-Mahdi Detention Centre: A Place for Murder and Mock Executions

According to a former political prisoner, this detention centre was built in 2005 or 2006 by the IRGC in a thoroughly modern style, and it is well-equipped. It has three corridors; in each corridor, there are six single and multiple-occupancy cells. The size of every single cell varies between 1.5 metres by 3 metres and 3 metres by 4 metres. It also has several multiple-occupancy cells with a capacity of 30 people. The bathrooms are separate from the cell, and each detainee has typically the right to go to the toilet three times a day. In all cells, there is a CCTV camera and all movements, and daily behaviours of detainees are monitored. In the ceilings of some of the cells, there are small windows with obscured glass, through which nothing can be seen. These windows are only occasionally opened by the guards for ventilation. The yard for taking fresh air is wholly covered with rebar. Usually, detainees are allowed to get fresh air for 15 to 20 minutes every day.

According to a Kurdish political activist who has been interrogated and tortured in this secret detention centre for several months, there are abandoned rooms outside the building of the detention centre where detainees are taken for torture. One of the most common forms of torture in this facility is the attachment of weights to the testicles of a detainee. In another form of physical torture common in this detention centre, detainees are hung from their hands to the ceiling for several hours, with arms fully stretched and only toes reaching the floor.

Another former political prisoner told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) that “There is a garden in the military compound of the Al-Mahdi detention centre next to the building of the Orumiyeh Military Court, and in some cases, the detainee is taken to this garden and tortured with a baton, hose, and stick. In several other cases, security interrogators manipulate the detainee by telling him they intend to shoot and execute him to obtain a forced confession. To carry out this type of torture, security interrogators tie the detainee’s hands and feet and take him to another area near the detention centre, where he gets told that he would be shot for not cooperating with the interrogators. Several armed people would also come to the scene, and the scenario continues with shots fired in the air or targeting the person’s legs until he confesses.”

Another political prisoner stated that the torture was not limited to the detainee himself and that security guards would detain the family members, especially his wife, to pressure him. He said: “After the interrogators failed to obtain my confession, they tried to force me to confess by creating psychological pressure. As a result, they arrested my wife and brought her to the detention centre. They then pressured me by saying they would rape my wife if I did not cooperate.” Several other detainees have also pointed out that interrogators threatened to abuse their family members, especially their sisters, mothers, and brothers, to obtain forced confessions.

In some cases, the detainee is held in solitary confinement for months without the right to receive visits or contact family. Mostly, the detainee cannot contact his family. With the consent of security interrogators, only in rare cases has the detainee been allowed to make phone calls for several minutes.

According to an investigation carried out by the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN), at least one Kurdish civilian has been tortured to death in this detention centre. Nasser Issazadeh, a resident of Salmas who has tried to join a Kurdish opposition party during his military service, was arrested in 2010 and tortured to death in this detention centre. IRGC forces have secretly transferred his body to his hometown and buried him at night.

Detention Centre of the Ministry of Intelligence in Sanandaj

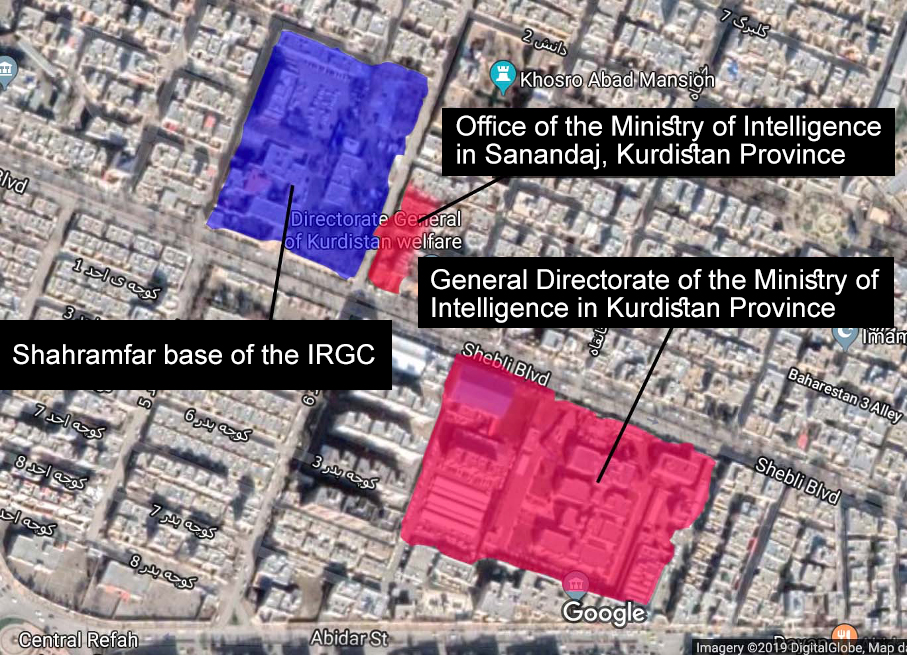

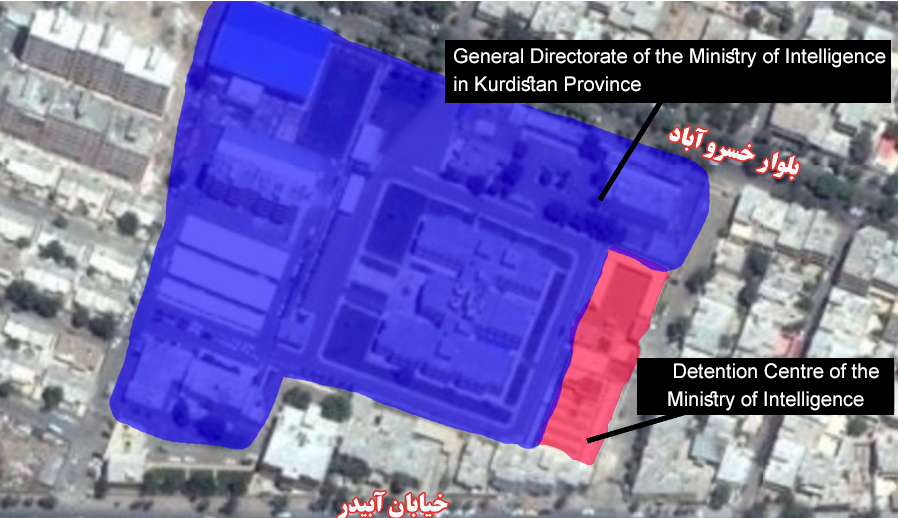

The detention centre of the intelligence ministry in Sanandaj is located in one of the city’s security areas, between two streets called Khosrow Abad Boulevard and Abidar, behind the Sanandaj Civil Registration Office in the premises of the General Office of the Ministry of Intelligence of Kurdistan province. Over the past few years, the intelligence ministry has blocked both sides of the alley leading to Khosrow Abad Boulevard and Abidar Street and monitors it under tight security measures.

Over the past few years, the office of the intelligence ministry in Sanandaj has installed cameras in most of the alleys near the detention centre, and the movement of people in this area is under strict control. Reportedly, due to the existence of special devices installed on the roof of the General Office of the Ministry of Intelligence, satellite signals and internet lines, up to a few kilometres of this place, are strongly disrupted.

The process of detaining takes place in two ways. Either a telephone call summons the person in question to the office of the intelligence ministry, which is located on Shebli Boulevard near the detention centre, and is detained at this location and transferred after being blindfolded and handcuffed, or the accused person will be transferred to the detention centre without prior arrest notice after being blindfolded and handcuffed by officers.

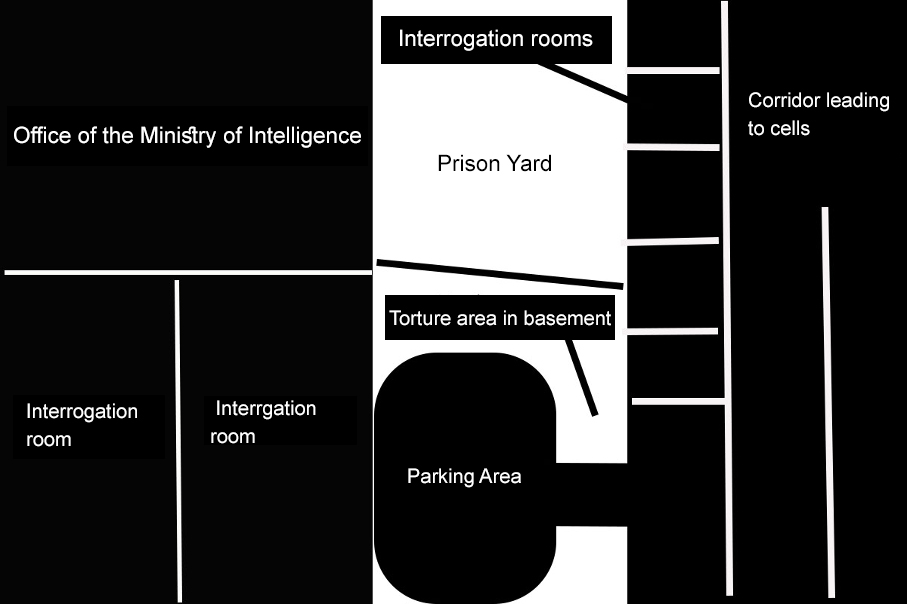

To confuse the detainee, these forces drive the detainee around the city for a long time and then take him to the detention centre from one of the entrance gates on Shebli Boulevard or Abidar Street. The building of this detention centre has been renovated over the past few years, and about 14 more cells have been added to it. The number of solitary confinement cells in this detention centre is estimated at 34 cells in five corridors.

According to information obtained by the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN), several changes have been made to this security detention centre over the past ten years. These changes include adding toilets and bathrooms in each cell, building new corridors consisting of single and multiple-occupancy cells, and removing the windows of all cells. The windows were removed in 2006, by order of the then director-general of this detention centre, after two detained citizens escaped using the window installed in the ceiling of their cell.

The detention centre had five main corridors. Over the past few years, a new one with 14 cells has been built behind them.

Similar to the other detention centres, detainees in this facility are tortured physically and psychologically in various ways. In the past few years, at least two detainees have lost their lives under torture. One of these people was Ebrahim Lotfollahi, a Kurdish student activist, arrested by security forces on 6 January 2006. Security forces buried him overnight in Sanandaj cemetery nine days later. Although officials of the Ministry of Intelligence in Sanandaj said he had lost his life due to suicide, his family and human rights activists found it suspicious and claimed he was tortured to death. His sudden burial without informing his family was proof of the claims of civil and human rights activists. After the suspicious death of Ebrahim Lotfollahi, several human rights activists published reports on a person named Hatefi, one of the interrogators of the Ministry of Intelligence, who they claimed to be Lotfollahi’s torturer.

Also, another young man from Sanandaj named Sarou Ghahremani was arrested during the nationwide protests in January 2018 in Sanandaj. His body was returned to his family 11 days later. Following the widespread news on Sarou Ghahremani’s death, state media reported that he had been killed during a police chase, but sources close to the Kurdish civilian’s family told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) that security forces arrested Ghahremani on the street in Sanandaj and 11 days later returned his body to his family. His body was buried in Sanandaj cemetery under tight security measures. Sarou Ghahremani’s mother, who was allowed to see her son’s body, told her relatives that the marks of the beatings and wounds on her son’s body were clearly noticeable.

A Kurdish civil rights activist who was arrested in 2016 and spent a month in the security detention centre of Sanandaj told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) about his experience. “Armed and masked agents of the intelligence ministry raided my house and arrested me. After searching the house, they took me into a car with handcuffs and a blindfold. After we arrived at the detention centre of the intelligence ministry of Sanandaj, I was beaten out of the car, taken up a few steps, and taken to a room. Someone came and asked a few brief questions. Then they took me to another room. They opened my blindfold. A soldier stood in front of me and told me to take off my clothes, ring, and watch. I did so, and he gave me prison clothes, and I wore them. Shortly afterwards, I was taken to solitary confinement, a small 2 metres by 2 metres room with two dirty military blankets inside; there was a toilet in the small corner of the cell, and the stench was nauseating and unbearable. Inside the cell, there was a dimly lit light bulb that was always on. The cell door had two wicket gates that were locked from the outside. They were opened during breakfast, lunch, and dinner hours to hand us food or blindfolds. During interrogation, a soldier would give me the blindfold through the wicket. After I closed my blindfold, he would take me to the interrogation room. During interrogations, they would beat me regularly if they did not hear the answers they looked for.”

Mohammad Hossein Rezaei, a former Kurdish political prisoner who was wounded and detained by the IRGC in 2011 and had spent several months in the detention centre of the intelligence ministry in Sanandaj, spoke to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) about the conditions of the detention centre and the torture he was subjected. He said: “After 29 days in detention at the Shahramfar detention centre of the IRGC, I was transferred to the detention centre of the Ministry of Intelligence. Although my leg had just been operated on, I was taken to the basement of this detention centre and tortured severely just because I had sung some anthems inside my cell. After taking me to the basement, the guards laid me down on a bed. Both my hands were tied to the corners of the bed, and my legs were tied. They whipped on the soles of my feet with a cable. I was beaten many times for various reasons, and as a result of this torture, my nose and several ribs in my chest were severely damaged.” According to this political prisoner, the agents pushed him down from the first steps during his transfer to the basement. He later realised that all those who were taken to the basement for torture were also pushed down.

Farzad Kamangar, a Kurdish teacher, executed in Tehran’s Evin Prison on 9 May 2010, wrote in one of his letters that “The detention centre of the intelligence ministry in Sanandaj has one main corridor and five separate corridors. They put me in the last room of the last corridor. They changed my location regularly until one day, the head of the detention centre and several others beat me for no reason and took me out of the cell. I was hit on the back of my head at the top of an 18-step staircase that led to the basement and the interrogation rooms. I fell, and my eyes went black, and they had dragged me down in that condition. I do not know how they took me down 18 steps. I opened my eyes. I felt severe pain in my head, face and side. When I regained consciousness, they punched and kicked me again. After beating me for an hour, they pulled me up the stairs, took me to the second corridor and a small cell, and threw me into it. Two people beat me again until I fainted once more.”

It is worth mentioning that Dr Roya Tolouei, a Kurdish civil rights activist who currently resides in the United States, was arrested by security forces in 2005. In an interview, she told the Daily Telegraph that she had been raped while in detention in this centre.

Detention Centre of the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC in Sanandaj, known as Shahramfar

The detention centre of the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC in Sanandaj is located in IRGC’s Shahramfar base on Khosrow Abad Boulevard. It is a high-security detention facility, and comprehensive information is not available from all its cells. It consists of two floors. The reception area is located on the ground floor. The interrogation rooms are on the first floor, and solitary confinement cells are on the second floor. An elevator is used to move detainees between the floors. The number of cells is estimated at 30 cells. The yard is also in a completely closed area and is located on the second floor.

A teachers union activist, who was arrested by IRGC intelligence forces in Saqqez in 2014 and spent 49 days in this security detention centre, spoke to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network. “After my arrest, I was directly taken to the building of this detention centre on Khosrow Abad Boulevard. Upon arrival, I was asked several short questions in a room in a building, and shortly afterwards, I was transferred to a building 20 to 30 meters away from the first building. I was taken to a room where I handed over my clothes and received prison uniforms. I also filled out a form with my personal details and general health status. I was led to the cell with my eyes closed. The dimensions of the cell I was transferred to were approximately 2 metres by 5 metres with an iron door and a smaller door on it for the necessary communication with the guard and the delivery of food, etc. There was a small rug, a blanket, and a pillow on the floor of the cell. The floor was covered with ceramic and was too hot. I asked them several times to lower the room temperature, but each time they ignored it. It was clear that they had deliberately raised the floor temperature. The cell had a window of 50 cm by 50 cm, covered with a mesh net and railing. And there was a light bulb that was on for 24 hours. At the quiet hours of the day, sometimes the voices of the people outside and the mosque could be heard. I had to knock on the door to go to the toilet, and a guard would guide me to the bathroom while my eyes were blindfolded. After I was done, I would go back in the same way. Once a day, with my eyes closed, I would be guided down to the yard for fresh air, which was an area of 5 metres by 5 metres and was about eight steps lower than where I was kept. From the position of this area, which had access to the stairs on both sides, I noticed that it was located exactly in the middle of the building. There is a corridor around the yard and then cells around the corridor with one entrance and exit to the whole building. The height of this yard was 4 metres, and the top of it was covered with a mesh net and railing. Its wall was full of prisoner writings, especially the lines that indicated the days they had spent here. After a quarter of an hour, I would be returned to the cell with my eyes closed.

The interrogation room was located almost near the entrance to the building, and the two ends of the corridor led to the interrogation room. The entrance door was an iron door located at the entrance to the corridors and next to the interrogation room. There was another room that was sometimes used for phone calls and haircuts. After 10 pm, no request, which was usually made by knocking on the door, was answered. My bladder was about to burst many times in the morning due to the need to use the toilet, but the guards did not open the door. The floor of the cell was so hot that it would frustrate me in a way that made me feel like I didn’t want to sleep. The only insulation between me and the ceramic was the rug spread out on the floor, which I would take near the iron door, hoping to take advantage of the coolness of the narrow opening under the door to sleep for some minutes. But as soon as I did that, the guard would come and warn me to take the rug to the end of the cell and tell me that I was not allowed to sleep there. The guard’s quick response to the slightest movement inside my cell convinced me that a camera must have been installed inside the room.”

Mohammad Hossein Rezaei, a former Kurdish political prisoner, ambushed by the IRGC forces in 2011 and was arrested after being shot in the leg by these forces, told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) about how he was held in this detention centre. “I was detained in this detention centre for 29 days in the worst conditions. While I was wounded, I was transferred directly to this detention centre without being taken to the hospital. I was subjected to severe physical and mental torture for 29 days to make a forced confession. In the early days, an IRGC doctor examined me but did nothing to cure me. As a result, my foot became infected and got verminosis. In addition to being deprived of any medical care, my both hands were tied behind my back several times by interrogators. I was hung in that situation from my hands, which caused my shoulder to dislocate. Another doctor later examined me. He stated that I should receive orthopaedic treatment as soon as possible. I was put in a car, and after a few minutes, we reached a nearby building, where I fainted. When I woke up, I noticed that my shoulder was bandaged. Despite my dire condition, the security interrogators continued to torture me, but the target of the torture was mostly my face. I was slapped and punched.”

Detention Centre of the Ministry of Intelligence in Kermanshah: Torture and Rape

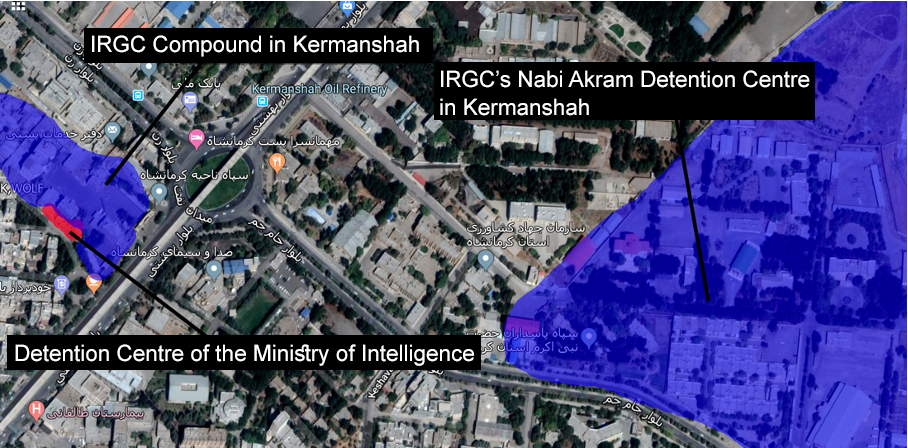

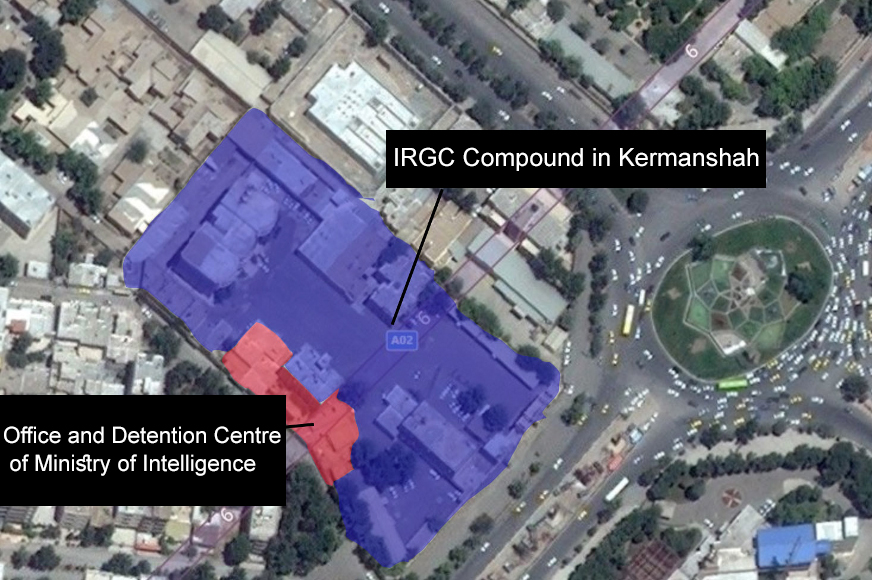

The Detention Centre of the intelligence ministry in Kermanshah, known as Meydan-e Naft Detention Centre, is located near the city’s oil refinery and next to the IRGC building in Kermanshah. According to a Kurdish activist who has been detained in this centre several times, the building of this detention centre dates back to before the Islamic revolution.

Unconfirmed reports indicate the construction of a newer detention centre in an alley near the Meydan-e Naft square, but, so far, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) has not been able to obtain accurate information on the location of the detention centre.

The critical point to note is that, unlike West Azerbaijan and Kurdistan provinces, most of the security interrogators in Kermanshah are natives of this province. The detention centre has two separate corridors equipped with cameras and has at least 15 large public cells. One of this detention centre’s cells, known as the multiple-occupancy cell, is 2.5 metres by 5 metres. There are also 1 metre by 2 metres and 2 metres by 3 metres cells. There is even a half a metre by half a metre cell. None of these cells has windows, and the detainee cannot distinguish day and night. There are two dirty blankets in each cell, and the cells do not have any heating or ventilation. Unlike detention centres in other provinces, there are no toilets or bathrooms in these cells. Each detainee has the right to go to the toilet three times a day.

This restriction is a method to put pressure on detainees. The detention centre has a large yard that is surrounded by two IRGC office buildings. It has a basement, where detainees are mostly taken for torture. There is a bed in the basement on which the detainee is laid and flogged with a cable. The people who work as guards at this detention facility are primarily old members of Basij forces trusted by the Ministry of Intelligence; several young guards have also been employed in recent years. After each detainee is handed over to these guards, they take the person to the interrogation room. After taking his photos, they take all his clothes. Then he wears a prison uniform and is transferred to a cell. Every day at 7 am, the detainees are awakened by a guard and returned to their cells after the toilet. After half an hour, breakfast is served inside the cells. If there are few detainees, their lunch and dinner are served in steel containers. Each detainee will have to wash the used container in the bathroom after eating. After breakfast, the interrogations begin. Detainees are usually allowed to use the yard and bathroom once a week. They do not have the right to shave their beards during the bath, and if they want to, their beards and hair will be shaved by the guards using a shaving machine after one month.

There are three interrogation rooms next to each other in the entrance corridor of the detention centre. At the end of this corridor, there is a room for the doctor. In exceptional circumstances that require an examination, the doctor of the Ministry of Intelligence examines the detainees in this room. In emergencies, the detainee is taken to a city hospital under tight security measures.

A detained activist who had committed suicide due to being subjected to psychological torture, and had been able to meet with the doctor once, spoke to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN). “I was under severe psychological torture for several months without the right to family visits and contact with them. To put an end to this difficult situation, I decided to commit suicide, and with great effort, I managed to lower the light bulb installed on the ceiling of the cell. I cut my wrist with the broken glass of the light bulb. The guards noticed it while serving dinner. As blood had covered the floor, they kicked and beat me while taking me to the bathroom in the hallway. That night until morning, I was tied to the radiator rods inside the cell. The next day, after my examination, the doctor hit me on the head with a pen and said, ‘There is no need to dress the wound. Let it be open so he would learn his lesson.'”

Zeynab Jalalian, another Kurdish political prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment and was interrogated and tortured for several months in this detention centre, spoke to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN). “After failing to obtain a forced confession, one of my interrogators stated that he wanted to temporarily marry me [in a procedure called Sighe or Nikah mut’ah]. So he tried to force a ring on one of my fingers. To prevent this, I had to kick him, which caused several people who were there to attack me and beat me to the point of losing my consciousness.” Zeynab Jalalian added that she was taken to the basement several times and was flogged on the soles of her feet by the interrogators for hours while lying on the bed. The lashes were so powerful that she had repeatedly fainted and been returned to the cell.

A Kurdish civilian arrested on charges of spying for the US intelligence service told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) that one of the tortures he and several of his co-defendants were subjected to was that they were forced to sit on a chair with a hole in it. Then heavyweights were attached to their testicles, and each time the weights were increased. Regarding the other tortures used in the detention centre, the detainee added that he was hung on the ceiling with a special rope for hours for several days. In this way, every time, he was hung for hours either from one hand, two hands from behind, or two legs.

Two women detainees also told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) that they had been tested for virginity by a doctor under pressure from interrogators. Another young woman arrested a few years ago on charges of spying for an intelligence agency affiliated with a political party in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq said that a detention centre cleric had raped her for several months. “After a week of detention, one day, two interrogators came into my cell and tied my hands and feet. Then they injected me with drugs using a syringe. At first, I resisted it, but I did not show any resistance after a few weeks. One day after the injection, I noticed a new person in the cell with my eyes blindfolded. After the greeting, I realised that his body was touching me, and I could feel his breath on my neck. I was suffering from moment to moment, but because my hands and feet were tied, I could do nothing but scream. He forcibly took off my clothes and raped me.” The young woman, who currently resides outside Iran due to security pressures, added that the only thing she saw from under her blindfold was that he was wearing a clerical robe. The cleric raped her continuously for two months.

Farzad Kamangar, a Kurdish teacher who was executed along with four other political prisoners in Tehran’s Evin Prison on 9 May 2010, had previously reported in his letters that he had been tortured in this detention centre. He wrote in one of his letters entitled Poetry, Night, and Torture: “In the winter of 2006-07, in cramped and dark solitary confinement in Kermanshah, without any charges, I endured a terrible imprisonment for three months, the three months after which, three years later, it still torments my body, soul, and spirit.”

Referring to his transfer from the cell to the basement, Farzad Kamangar described his torture as follows:

“It was a dark night, and a narrow, dark, and dank room with a small door that opened to the future on one side and the past on the other, and I was whispering a poem against the walls. There was an oppressive prison in me that never got used to the sound of its chain, the knocks on the door, disturbed my night dream and shattered the rhyme of my mother’s unwritten lullabies that I was whispering… Wear the blindfold, hands forward, handcuff! …Walk. They pulled me out of my little cell, I knew my way, better than the old guards who were as worn out as the cell doors. I knew better than my interrogators the number of the stairs leading to the basement under the yard. It was as if I had lived in this prison for years. I could even see the footprints of prisoners before me. While walking down the stairs, I would count the number of the feet of those present under the blindfold, one… two… three… four… five… six… They had come to exert their power on one person, and when I was standing, a poem was whispering to me, “God, where on earth am I standing…” and with the first blow, the poem remains unfinished, and I get tied to the bed… how scared I was… not from the pain of the lashes, from the fact that in the 21st century, in the century of dialogue, in the global village, people still whip and triumph over the suffering human body and laugh.”

Detention Centres of the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC in Kermanshah

The Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC has several high-security detention centres in the city of Kermanshah. Due to tight security measures, the exact location of these detention centres is unknown. After several months of investigation, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) has only obtained information about one of these detention facilities in the IRGC’s Nabi Akram base in Kermanshah. A detainee transferred to a secret IRGC detention centre for 24 hours for interrogation spoke to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN). “After my arrest, they took me to a building with a large garden in its courtyard. They took me to a cell. Inside the cell, a camera and a bell were used to alert the guard for going to the bathroom. It was clear from the condition of the building that it was newly built. There were also female officers in the detention centre.”

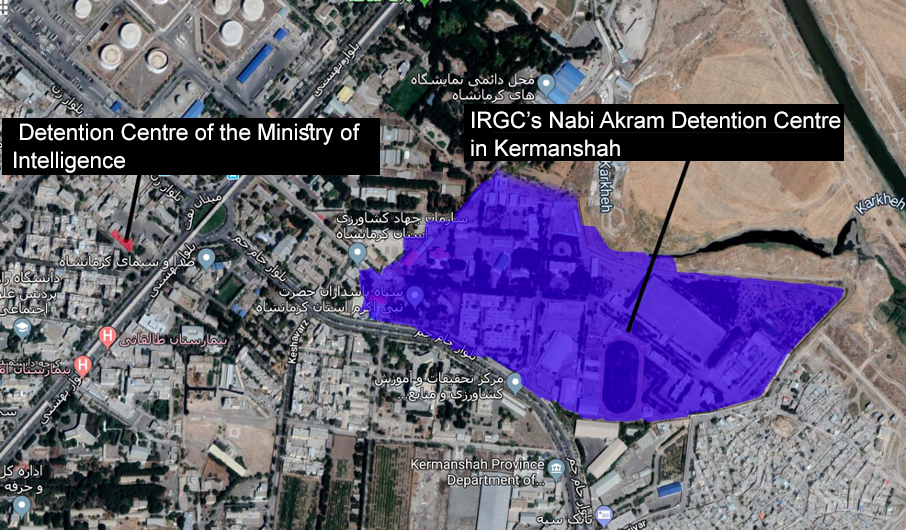

IRGC’s Nabi Akram Detention Centre in Kermanshah

This detention centre is newly built and is located in the IRGC’s Nabi Akram base in Kermanshah, near Naft square. Several Kurdish activists who the Intelligence Organisation of the IRGC had detained in Kermanshah told the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) that after being transferred to the detention centre, they were taken to a reception room next to the guardroom, where all their personal belongings and clothes, except for underpants, were taken. They were then taken inside the cell wearing prisoner uniforms.

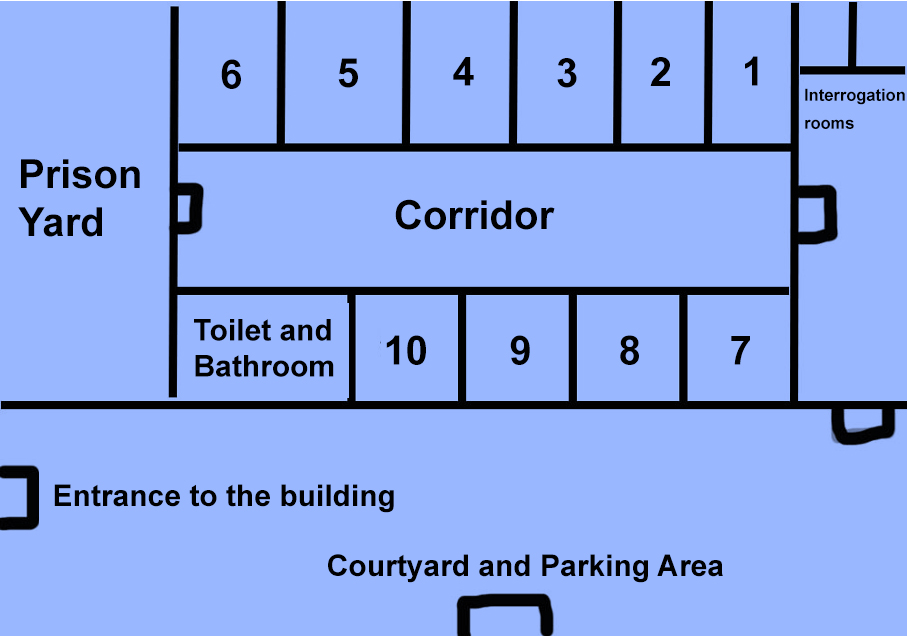

Part of this detention centre has a hall that has six cells on the right side and four cells, two rooms, a bathroom, and a toilet on the left. These cells are 9 metres by 15 metres and do not have ventilation. Only through the wicket gates used to deliver food, cool and hot air enter all the cells. At the end of this hall, next to the toilet and bathroom, there is an entrance door to the yard, the top of which is completely covered with rebar and metal cover.

According to the detained activists, there are cameras in some of these cells that allow the guards to observe the movements of each detainee. The floor of each cell is covered with carpet, and two old blankets and a water flask are given to each detainee.

The detention centre has two interrogation rooms, and detainees are interrogated behind an obscured glass. The only torture report in the detention centre was published in an open letter by the executed Kurdish political prisoner Hossein Khezri. In this letter, he explained his detention and the torture inflicted on him in this detention centre. “I was arrested by the IRGC forces of Nabi Akram in Kermanshah on 31 July 2008. I was subjected to all kinds of physical and mental torture during the interrogation for the 49 days that I was in custody in the Nabi Akram base of the IRGC in Kermanshah. Physical tortures included beatings for several hours every day, psychological pressure during the interrogation, threats by interrogators that if I did not accept what they said, they could label my brother and family’s son-in-law as people carrying out illegal activities against the state, kicking my genitals which resulted in bleeding and swelling for 14 days, the rupture of my right leg about 8 cm, which is still visible, due to the interrogator’s strong kick, and multiple blows to my entire body with a baton. These took place during the 49 days of my detention in the detention centre of the IRGC in Kermanshah.”

Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN)

The Kurdistan Human Rights Network is an independent, non-profit, and nonpartisan organisation registered in France since 2014.

The activities of this organisation focus on the two areas of education and promotion of human rights principles and values, as well as reporting and documenting human rights violations in Kurdistan/Iran.

Our activities also consist of raising public awareness and informing the media, as well as international human rights institutions and organisations. In this regard, the website and official social media accounts and channels of the Kurdistan Human Rights Network are active in three languages: Kurdish, Persian, and English.

The Kurdistan Human Rights Network has been a member of the World Coalition Against the Death Penalty since 2017. It also has close ties and bilateral cooperation with Kurdish, Iranian, and international human rights organisations.

Kurdistan Human Rights Network

www.Kurdistanhumanrights.net

Info@kurdistanhumanrights.net