Joint explanation of the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (Network) and the “Abdorrahman Boroumand Center for Human Rights in Iran (ABC): This case is a part of the collaborative documentation of the Kurdistan Human Rights Network and the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center. The Kurdistan Human Rights Network intends to gradually document cases of extrajudicial executions of Kurdish citizens and activists. For this purpose, the network has used the experiences and research methodology of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center, which has been active in the field of documenting human rights violations in Iran for many years. The report of this case and subsequent reports will be published in the “documentation” section of the Kurdistan Human Rights Network website and the “Omid Memorial” of the Abdorrahman Boroumand Center. Some of the original and follow-up interviews used in this documentation were conducted by the Center, some by the Network, and some in collaboration.

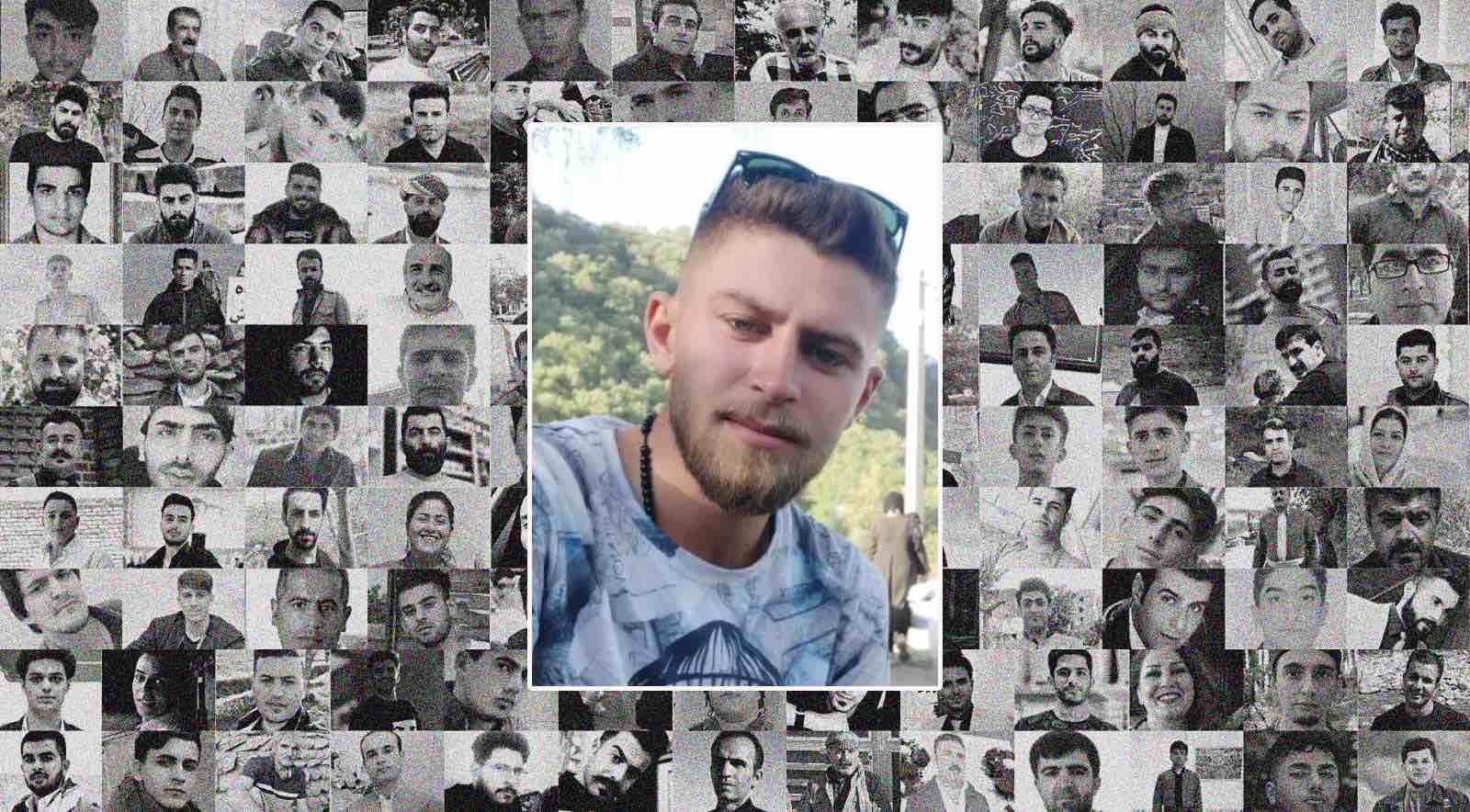

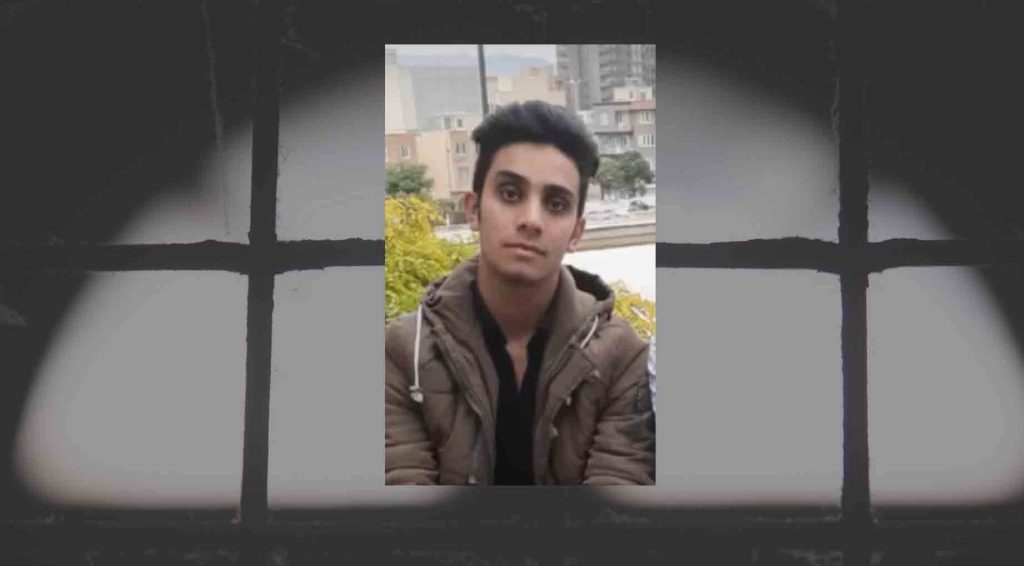

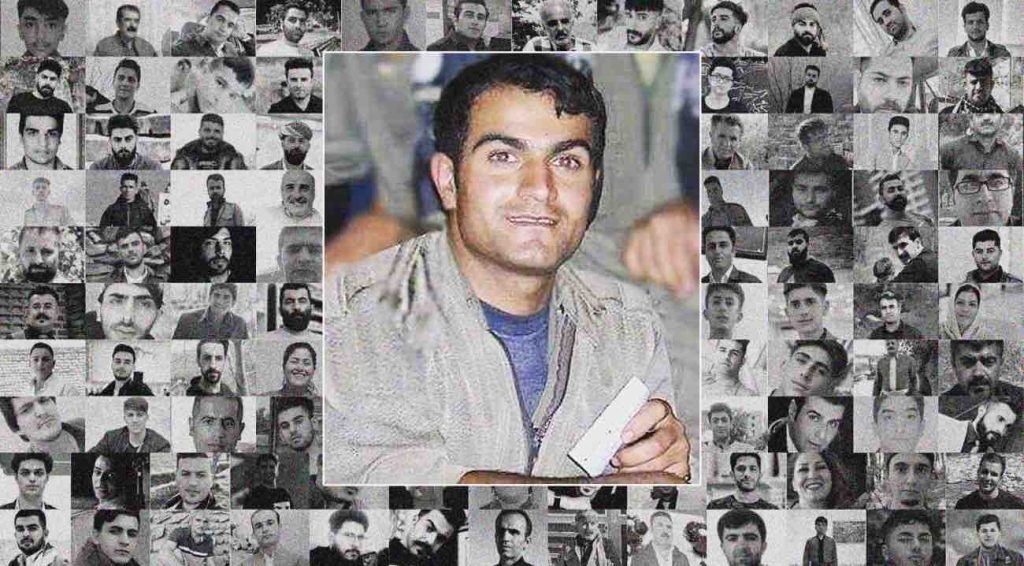

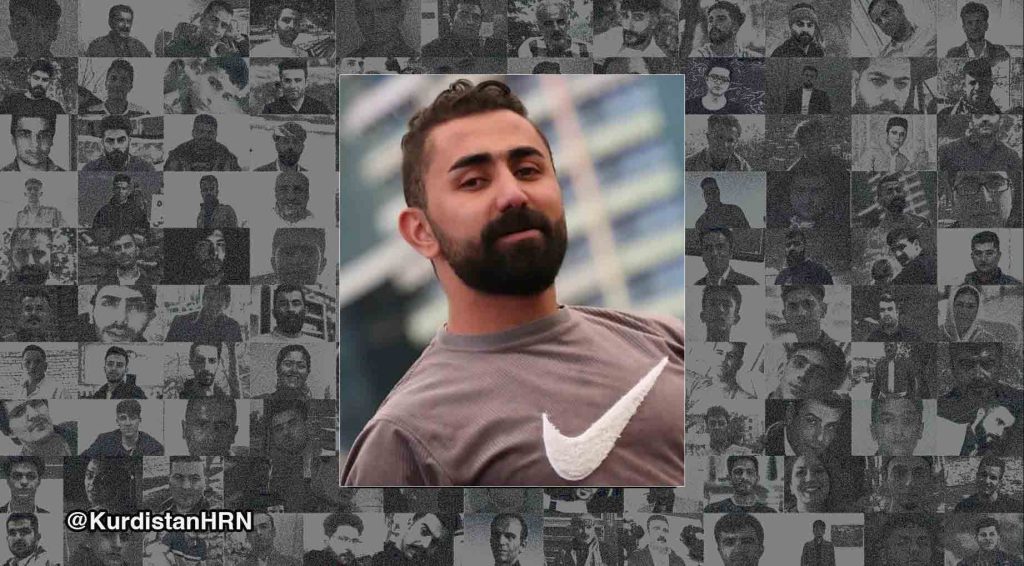

Information about the extrajudicial execution of Mr. Ayoub (Rebaz) Salehivand, son of Abdullah Salehivand and Khadija Aramidehnia, was obtained via interviews on two different occasions with one of the family’s relatives (March 4, 2022, and September 6, 2023) and another, with one of his friends (August 21, 2023). To complete this case’s information, the material was obtained from Mr. Salehivand’s personal Instagram page, Kurdistan Human Rights Network reports (November 23, 2022), BBC Persian on X social media network, formerly known as Twitter (November 23, 2022) and Mr. Salehivand’s death certificate.

Mr. Salehivand was born on September 30, 2002, to a Kurdish and Sunni family. He spent his childhood and elementary education in Yusefkand village, Mahabad Township, in West Azerbaijan Province. According to one of Mr. Salehivand’s close relatives, given that his “interests” did not correspond with the “scholastic system,” he dropped out in the last year of high school and turned to industrial jobs. He was a construction rebar master and worked with his uncle. Mr. Salehivand was also interested in tattooing. He was self-taught and learned the art of tattooing from his friends (Interview with a relative, February 20, 2023).

In the summer of 2022, as the protests against the murder of Jina (Mahsa) Amini took off, despite his family’s opposition and the violence of the security forces, Mr. Salehivand participated in many demonstrations. According to one of his relatives, in response to his family’s opposition to his participation in the protests, he said: “It doesn’t matter what happens to me; if we don’t go, who will go to the protests? It is my responsibility and duty to participate.” According to the interviewee, he and other protesters lit a fire on the main Mahabad-Orumieh road near his village during one of the protests (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

According to the same source, Mr. Salehivand had a “very fearless and courageous” personality, was interested in Kurdistan’s political issues, and was familiar with “Kurdish history and the region.” He was also an “introvert,” and his speech was measured (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

2022 (Mahsa Amini) Protest background

Nationwide protests were sparked by the death in custody of 22-year old Kurdish woman Jina (Mahsa) Amini on September 16, 2022. Amini had been arrested by the morality police in Tehran for improper veiling on September 13 and sent brain dead to the hospital. The protests, which started in front of the hospital and continued in the city of Saqqez (Kordestan Province), where Mahsa was buried, were triggered by popular exasperation over the morality patrols, misleading statements of the authorities regarding the cause of Mahsa’s death and the resulting impunity for the violence used against detainees, as well as the mandatory veil in general. This protest, initially led by young girls and women who burned their veils and youth in general who chanted the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom,” rapidly took on a clear anti-regime tone, with protesters calling for an end to the Islamic Republic. The scope and duration of the protest was unprecedented. State efforts to withdraw the morality police from the streets and preventative arrests of journalists and political and civil society activists did not stop the protests. By the end of December 2022, protests had taken place in about 164 cities and towns, including localities that had never witnessed protests. Close to 150 universities, high schools, businesses, and groups including oil workers, merchants of the Tehran bazaar (among others), teachers, lawyers (at least 49 of whom had been arrested as of February 1st, 2023), artists, athletes, and even doctors joined these protests in various forms. Despite the violent crackdown and mass arrests, intense protests continued for weeks, at least through November 2022, with reports of sporadic activity continuing through the beginning of 2023.

The State’s crackdown was swift and accompanied by intermittent landline and cellular internet network shutdowns, as well as threats against and arrests of victims’ family members, factors which posed a serious challenge to monitoring protests and documenting casualties. The security forces used illegal, excessive, and lethal force with handguns, shotguns, and military assault rifles against protesters. They often targeted protesters’ heads and chests, shot them at close range, and in the back. Security forces have targeted faces with pellets, causing hundreds of protesters to lose their eyesight, and according to some reports women’s genitalia. The bloodiest crackdown took place on September 30th in Zahedan, Baluchestan Province, where a protest began at the end of the Friday sermon. The death toll is reported to be above 90 for that day. Many injured protesters, fearing arrest, did not go to hospitals where security forces have reportedly arrested injured protesters before and after they were treated.

By February 1, 2023, the Human Rights Activists News Agency reported the number of recorded protests to be 1,262. The death toll, including protesters and passersby, stood at 527, of whom 71 were children. The number of arrests (including of wounded protesters) was estimated at 19,603, of whom 766 had already been tried and convicted. More than 100 protesters were at risk of capital punishment, and four had been executed in December 2022 and January 2023 without minimum standards of due process. Authorities also claimed 70 casualties among state forces, though there are consistent reports from families of killed protesters indicating authorities have pressured them to falsely register their loved ones as such. Protesters, human rights groups, and the media have reported cases of beatings, torture (including to coerce confessions), and sexual assaults. Detainees have no access to lawyers during interrogations and their confessions are used in courts as evidence.

Public support and international solidarity with protesters have also been unprecedented (the use of the hashtag #MahsaAmini in Farsi and English broke world records) and on November 24, 2022, the UN Human Rights Council adopted a resolution calling for the creation of a fact finding mission to “Thoroughly and independently investigate alleged human rights violations in the Islamic Republic of Iran related to the protests that began on 16 September 2022, especially with respect to women and children.”

The context of Mahabad Protest

Mahabad was one of the most important epicenters of the “Women, Life, Freedom” uprising. Protests in Mahabad continued for months, and an oppressive security atmosphere presided over this city. During these protests, at least 12 protesters were killed by security and military forces in Mahabad; several protesters were arrested, many of whom were injured.

Mr. Rebaz Salehivand’s death

Mr. Rebaz Salehivand was shot by the security forces on the morning of Tuesday, November 22, 2022, near the village of “Haji Mamian” in Mahabad, and died a few hours later due to the severity of his injuries (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023, Kurdistan Human Rights Network reports, November 22 and 23, 2022).

According to one of the relatives, Mr. Salehivand was previously monitored by an individual affiliated with the security forces who approached him under the pretext of friendship (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023). According to one of Mr. Salehivand’s friends, this individual from the village of Yusefkand, who Mr. Salehivand had met at work, had concocted a plan to befriend Mr. Salehivand during the 2022 protests; he visited Mr. Salehivand at his place of work often and was, therefore, able to keep tabs on him (Interview with one of his friends, August 21, 2023). Mr. Salehivand told his family in the days leading up to his killing that he felt his name and details had been “reported” to the security forces. He also believed that “while burning tires to block a street during the Mahabad protests,” as well as “during the attack on the home of a local member of the Revolutionary Guards,” he was filmed (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023)

According to the same source, the night before he was killed, Mr. Salehivand had told his family that due to fear of arrest, he and a friend were planning to stay at his grandmother’s house in Mangurayati district for a while. According to footage recovered from cameras along the road, which belonged to private house gardens, Mr. Salehivand, instead of going to work, rode a motorcycle along Haji Mamian Road in Mahabad with the individual posing as his friend in tow. They drove in the direction of Mangurayati. But to go to this destination, he should have taken a different route than the area where he was killed (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

The exact time and manner of Mr. Salehivand’s murder unclear, but the only person accompanying him called Mr. Salehivand’s father around 11:15 a.m. and informed him that his son Ribaz had been injured. When Mr. Salehivand’s father arrived on the scene, he was still alive and could breathe, though his body was covered in blood. Fearing arrest, the family took their child to his grandmother and grandfather’s house in Mahabad instead of the hospital. As the family was getting medical support, Mr. Salehivand died due to the severity of his injury (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

Mr. Salehivand’s companion claimed that they were attacked by the passengers of two Peugeot “GLX” automobiles with tinted windows and a beige 3F vehicle near the village of Mazra, next to an iron fbridge on the way to a military barracks. However, there is no evidence to show that Mr. Salehivand was shot while he was on the motorcycle. According to one of the relatives, dozens of pellet gunshots hit Mr. Salehivand’s back, but certainly, none of the bullets hit Mr. Salehivand’s companion, and there were no gunshot marks on the motorcycle. Additionally, while washing Mr. Salehivand’s body, other than the dozens of bullet wounds on his body, they noticed that “he had a contusion on his head and that there was a blow to his abdomen” (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023, and September 5 and 6, 2023).

In the death certificate, the cause of Mr. Salehivand’s death is stated as “collision with hard or sharp objects” (archive documents).

Mr. Salehivand’s body was buried in the Yusefkand village of Mahabad on Tuesday, November 22, in the presence of family members, acquaintances, and a large crowd of people, despite the restrictions of the IRGC forces (BBC Persian Twitter, November 23, 2022, Kurdistan Human Rights Network Twitter, November 23, 2023).

Mr. Salehivand was only 21 years old at the time of his murder.

Official Reaction

According to one of the relatives, IRGC forces surrounded Mahabad’s city entrance and prevented them from burying him in Bagh-e Ferdows in this city; the family was forced to bury Mr. Salehivand in the Yousefkand village cemetery, a few kilometers from Mahabad (Interview with a relative, November 23, 2022, Kurdistan Human Rights Network channel, November 23, 2022).

The intelligence officers of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, who were sent from Tehran to Orumieh, summoned his family members a few days after Mr. Salehivand’s funeral. These officers interrogated them in front of cameras for eight days (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

According to one of the relatives, during the interrogation of the family members, the IRGC agents claimed that Mr. Salehivand played the role of “leader” in the Mahabad protests (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

According to the interviewee, the individual who was with Mr. Salehivand at the time of the murder has not been seen again since the fourth day after the burial (Interview with a relative, March 4, 2023).

Family’s Reaction

There is no accurate information about Mr. Salehivand’s family’s reaction to his murder. According to the videos released from the funeral ceremony, his father, Mr. Abdullah Salehivand, after calling for the establishment of an independent Kurdistan, said, “Today my son was martyred, but tomorrow it will be your children’s turn.” He also condemned the “collaboration of Kurdish forces with security institutions in shedding the blood of Kurdistan’s youth” (Telegram of Kurdistan Human Rights Network, November 23, 2022).

Impact on the family

There is no evidence of the effect of Mr. Salehivand’s murder on his family members.