By Awat Pouri

Introduction

According to the Open Data Website of Iran, an average of 21,000 hectares of forests and pastures in Iran burn annually. Based on the statistics of the Green Association of Chiya of Marivan, in the latest fire that occurred from August 12 to 16 in the forests around Marivan, two thousand and thirty-five hectares were burnt. This is while government authorities had reported the burning of nearly one thousand hectares of these forests in July. These same authorities have confirmed that in the first half of 2023, more than three thousand hectares of forests in Kurdistan province have been burnt. However, reports from the Green Association of Chiya indicate that in the first six months of 2023, more than five thousand hectares of these forests around Marivan have been burnt.

The rate of forest and pasture destruction in Iran, broken down by provinces, shows that in recent years, the forests of the two border provinces, predominantly Kurdish inhabited Kurdistan and West Azerbaijan, have witnessed the most fires. According to official statistics, over 14% of the forest and pasture fires in the first half of this year occurred in the Kurdistan province, which only comprises 1.3% of Iran’s forests and pastures. This is while independent environmental associations report significantly more fires than what the official statistics claim. On the other hand, authorities and officials of the Kurdistan province’s natural resources and environmental departments confirm this. At least two high-ranking provincial government officials cited human intervention as the main cause of the recent Marivan forest fires.

In general, the causes of forest and pasture fires can be divided into environmental and human factors. Drought, hot weather, and soil erosion are among the environmental factors. This research focuses on human factors, including deliberate actions, pre-fire management negligence, and delays in controlling fires after their occurrence. According to gathered evidence, governmental institutions responsible for protecting forests and pastures have often intentionally created conditions for unintentional fires caused by human factors. Environmental activists and local witnesses state that these institutions have ignored their numerous reports identifying and reporting wood smugglers and tree-cutting violators. This has allowed offenders to freely and fearlessly destroy forests, further exposing them to accidental fires.

In this research, the delay of responsible institutions in controlling forest fires in these regions has also been addressed. According to local environmental activists and residents of these areas, not only have government institutions failed to take immediate and timely actions to control the fires, but they have also used force to prevent the dispatch of volunteer civilian forces and have arrested environmental activists and organizers of these civilian forces.

Another section of the report examines the motives and objectives of government institutions behind such actions. The movements, mine-laying, shelling, deployment of heavy military equipment, and maneuvers of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s military forces, particularly the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, under the pretext of ‘cleansing’ these areas from Kurdish opposition party forces, are among the evidence supporting the hypothesis of security motives behind the destruction of forests in these regions.

The purpose of this research is to determine the role of government-affiliated human factors in the forest fires of Kurdistan province, focusing specifically on the case study of the Marivan forest fires in August of this year. Raising awareness about the complex dimensions and long-term consequences of these fires on the environment and society is another issue of this research. Among the most serious consequences are the weakening of civil society in Kurdistan, particularly in Marivan around the topic of environmental protection, and the depopulation of the border areas of Kurdistan for their militarization.

The significance of this report lies in clarifying the ambiguities regarding the relationship between the activities of governmental and judicial institutions in setting the stage for fires. It also uncovers the actions of security and military institutions in delaying fire control, preventing volunteers and activists from firefighting, and in some cases aiding the spread of fires by flying helicopters in the direction of fire movement. This report aims to analyze the security motives behind these actions.

Questions

What are the main factors causing forest fires? What role does each of these factors play in the occurrence of the Marivan forest fires? What proportion of human factors consists of deliberate interventions or managerial negligence? Are these negligences planned and carried out with specific objectives? Who are involved, and what institutions lay the groundwork for deliberate fires? What is the role of political conflicts and security conditions in Kurdistan in these fires? What are the long-term consequences of the fires on the ecosystem and civil society of Kurdistan? What benefits do the fires bring to the security and military institutions of the government?

Methodology

This report focuses on the recent fires in the forests of Kurdistan, especially Marivan. For this purpose, news and reports from government media about the Marivan fires in July and August this year have been continuously monitored, and the statements and reactions of relevant officials have been collected and analyzed. Additionally, reports, interviews, and positions of activists and environmental protection organizations both inside and outside the country have been considered and referenced as necessary.

Most of the data and statistics cited in this report have been collected and analyzed through research in open-source intelligence.

To resolve some ambiguities and contradictions surrounding the suspicious fires in Kurdistan, interviews were conducted with members of the board of the Green Association of Chiya of Marivan. These conversations aimed to utilize evidence and documents specifically gathered and documented by the members of this association. The analysis and personal experiences of the members of the “Zagros Environmentalists Association” in dealing with the Marivan forest fires and their differences with other areas are also reflected in this report.

“Ammar Goli,” a journalist and analyst on Kurdistan issues, is another interviewee in this report, providing insight into the security motives behind these fires. Additionally, a resident of “Doploreh” village, located in the path of the fire, has been interviewed.

“Mansour Sohrabi,” an agroecologist (expert in ecology and environment), is among the experts consulted to discuss the vegetation cover of Marivan forests and its impact on the fires.

Examining and referencing the available visual evidence of human intervention in the initiation of the Marivan fires has also been a part of the process to reach the findings of this report.

Limitations in Research

The pressure exerted by security institutions on environmental activists in Kurdistan has created an atmosphere of terror and fear surrounding the issue of forest fires. Even simple environmental activities in Kurdistan face harsh reactions from security institutions, making organizations and individuals reluctant to disclose documents and evidence indicating the role of government agents in these fires. Consequently, accessing these documents is challenging, and participation in research on this subject is often contingent upon sources leaving the country.

Another challenge of this research is the efforts of government-controlled media to spread rumors and disseminate misinformation about these fires. These media outlets, by continually emphasizing the presence of “armed Kurdish parties” in these areas, have shaped a unipolar and pervasive narrative that paves the way for various rumors to justify deliberate fires. This narrative has significantly influenced the sensitivity of Iranian civil society towards this issue.

Findings

Chain forest fires in the Zagros forests started in the mid-2000s and have been increasing since then. The findings of the report indicate that natural factors cannot be the cause of any of the forest fires in the Zagros, a fact that is especially true in the case of Marivan, which has been studied here. According to experts, these factors only play a role in exacerbating and spreading the fires, not in starting them.

According to the Green Association of Chiya, in the year 2020, at least 188 forest fires occurred in the forests surrounding Marivan and Sarvabad. Another report from this association states that the number of forest fires in Marivan and Sarvabad in 2021 increased by more than 13 times compared to the previous year. As mentioned by one of the board members of the association, this number reached over 330 cases in the first half of 2022 alone, not including the fires around Sarvabad. In fact, the start of these chain fires from a specific time and their frequency and density in certain parts of the Zagros, negate any possibility of natural factors being involved. “In ecology and geography, scale determines the nature and name of a phenomenon and can transform it from an event to a condition,” which is clearly observable in the case of the Marivan forest fires.

Statements from environmental activists, experts, witnesses, and journalists confirm that over 95% of the fires are caused by deliberate human factors. These include parts such as deforestation for changing the land use of forest areas to agricultural, garden, residential, and commercial lands, or cutting trees for charcoal production and wood smuggling, and military and security factors like maneuvers, explosions of mines left from the eight-year war, and mines planted by military organizations in past years under the pretext of preventing the infiltration and entry of Kurdish opposition forces.

The forest breathing plan for the northern forests of the country was first proposed in 2012 by “Masoumeh Ebtekar,” the former head of the country’s Environmental Protection Organization, and was later approved by the Islamic Consultative Assembly with some modifications. Environmental activists and experts interviewed in this report unanimously agree that the implementation of this plan has unprecedentedly directed the wood smuggling and charcoal production mafia towards the forests of Kurdistan.

According to one of the members and founders of the Zagros Environmentalists Association, which primarily operates in Marivan, with the initiation of the Alborz Forests Breathing Plan, what he calls the “wood smuggling mafia” under the guise of large companies, poured into this region and started massive illegal exploitation of the Zagros forests. Other reports confirm that the felled trees are transported to large wood mills in the north of the country or to a paper mill in Tabriz. These reports indicate that small-scale violators are not directly connected with these factory owners and sell the trees to known middlemen in the region. It is said that the secondary occupation of most people in the villages around Marivan is cutting trees and selling them to these middlemen.

A long-standing member of the board of the Green Association of Chiya confirms that violators freely cut down centuries-old trees in the Marivan forests at any time of day or night, passing large shipments of wood and charcoal through checkpoints without any hindrance or restriction to their destinations.

He states, and this is also confirmed by the Green Association of Chiya and endorsed by responsible provincial institutions, that in the fire of August this year alone, more than 1,065 hectares of oak forests around Marivan burned. This is only a part of the total 2,035 hectares that were completely destroyed during those days. He says that in the first half of 2022, more than 5,000 hectares of forests around Marivan burned, while the current total area of Marivan’s forest lands is 100,000 hectares. Looking at government statistics, this area is still estimated to be between 170,000 to 185,000 hectares, which seems to be based on figures before the chain of fires that started in the mid-2000s. A simple comparison of these figures reveals that in a period of about 15 years, more than 70,000 hectares of Marivan’s forest lands have fallen victim to the flames.

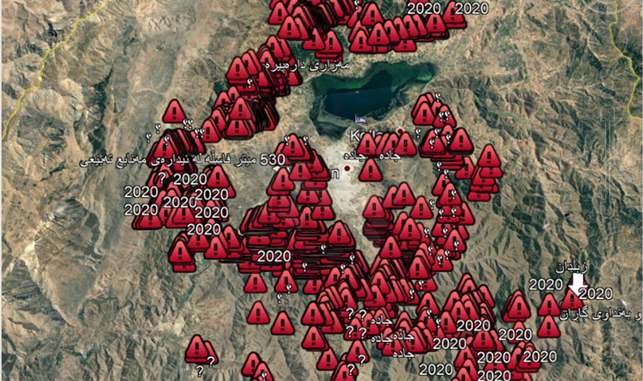

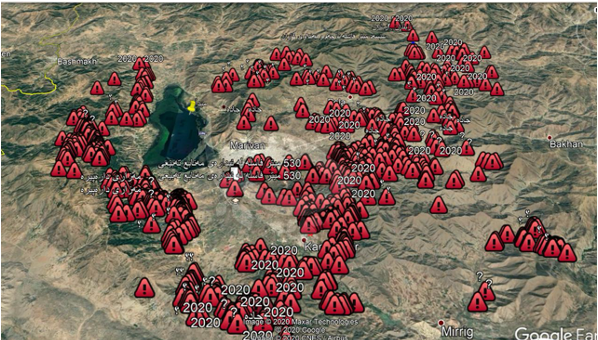

Over the past years, the Green Association of Chiya has initiated a campaign to identify, collect, and publish the geographical coordinates of areas being destroyed by human activities. According to a senior member of the association, in just one instance, a list of 1,300 specific points was formally submitted in letters to the Director-General of the Judiciary of Kurdistan Province, the Head of the National Crisis Management Organization, the Head of the National Natural Resources and Watershed Management Organization, the Head of the Environmental Protection Organization, and several other institutions and organizations. However, not even in a single case has any action been taken against the violators. He says that this list represents only a small portion of all the cases they have collected and documented.

A senior member of the Zagros Environmentalists Association also confirms that the judiciary is completely indifferent in this matter. According to his information, there are at least 500 to 600 cases of violators involved in tree cutting and charcoal production in the Marivan judiciary, of which perhaps only three or four have received two to three-month prison sentences. He knows of violators who, despite being convicted in cases involving several hundred tons of wood smuggling, have been acquitted and released by only paying fines of four to five million tomans and have even reclaimed their smuggled cargoes.

This is in stark contrast to the law against goods smuggling, which states, “Individuals who are considered professional wood smugglers, in addition to the confiscation of the smuggled wood, are subject to a maximum monetary fine, 74 lashes of disciplinary flogging, and imprisonment from 91 days to two years.”

The number of civil and environmental protection organizations in Marivan is not small. Each of these organizations, with all their resources and capabilities, is striving to prevent these fires. However, according to senior members of two well-known organizations in this city, not only is there no will on the part of responsible government parties to prevent the fires, but evidence and indications suggest that violators in this region are being completely left to their own devices.

Our findings indicate that the destruction and seizure of forest lands in Marivan occur in three distinct geographical areas with different objectives and motivations. The border areas, comprising most of the pastures of the Marivan district, are entirely under the control of military forces associated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps or border guard and border regiment forces affiliated with the law enforcement forces. Seizure, fencing, creating no-entry zones, and destruction of forests by these agencies are carried out under security pretexts such as countering activities and infiltration of Kurdistan opposition parties.

Environmental activists and residents of the forest areas near the borders testify that these forces consider themselves entitled to shoot if non-military personnel enter these areas. In fact, entry into these areas equates to the risk of being shot, as seen with porters in other border areas who are regularly targeted by these forces. Therefore, unrelated individuals or groups cannot be responsible for the destruction of forests and the burning of border pastures. The control of movement to these areas is so strict that even environmental activists and volunteer forces are not exempt during fires and are arrested as soon as they cross the designated borders. Military forces stationed in these areas may also destroy large sections of these forests for their major projects, which are neither traceable nor is questioning about them wise in the current environment.

The second area is the forest lands near the center of Marivan city, where perpetrators, after burning the forests, proceed to uproot the burnt trees. They then divide the burnt lands into smaller plots, register the lands officially without any restriction from the responsible institutions, and put them up for sale or start construction on them.

The third category includes areas slightly farther from the city center towards the east and to some extent north of Marivan. (Moving away from the city center towards the west leads to border areas under full control of military organizations.) These regions are usually destroyed with the intention of converting forest lands into agricultural lands or for orcharding. One of the reports by the Green Association of Chiya, published in January 2021, which identified and recorded 650 cases of forest destruction, shows that most of the fires in this area occur there. An interesting point in this report is that more than a hundred of these cases occurred within a ten-day period.

In April of the same year, Chiya reported in another document the identification of 1,200 cases of forest destruction in Marivan and Sarvabad, and published satellite imagery of it.

Cutting down trees for charcoal production is one of the main factors destroying the forests in Kurdistan province and Marivan city. The CEO of the Green Association of Chiya, in an interview after the widespread fire in August of this year, warned about the existence of more than 1,200 charcoal kilns around Marivan. According to him, the efficiency of non-industrial charcoal production, which is prevalent around Marivan, is only 25%, meaning that burning every 100 kilograms of wood yields about 20 to 25 kilograms of charcoal, while the efficiency of industrial charcoal production is 75 to 80%.

Mohammad Naji Kani Sanani stated in this interview that 12 to 15 villages in Marivan are located along the path of the Zagros oak forests. “In each of these villages, about 20 people are engaged in charcoal production, and each has five kilns or pits. This way, the contribution of each village amounts to 100.” Based on this, the number of non-industrial charcoal kilns in these few villages is estimated to be between 1,200 and 1,500, which seems a very high number for such a small area.

He says that this issue is not hidden from anyone. The natural resources and environmental departments and institutions like village councils and district offices are fully aware, or if not, have been informed through the reports of the Green Association of Chiya. However, they not only show no will to stop charcoal production, but they have also not taken any steps to transition from non-industrial to industrial methods of charcoal production, which alone could prevent a significant portion of the damage to the forests.

Our searches on the internet and web pages show that not only is there no obstacle or limitation for charcoal production in the forests of Marivan, but there are also numerous pages and websites that openly advertise the establishment of charcoal production lines in this district, along with offering consultation, investment, and initial tools and equipment for free.

The findings of the report up to this point indicate that almost no action is taken by responsible institutions to prevent fires before they occur. However, the story does not end here, and the negligence, laxity, and in some cases, cooperation of these institutions with violators continues in various forms after the fires.

A board member of the Green Association of Chiya, who jokingly compares the actions of the Kurdistan province and Marivan district Natural Resources and Watershed Management Department for fire extinguishing, says that the Green Association of Chiya was not established in 1999 with the sole purpose of extinguishing oak forest fires. Combating fires is one of the hundreds of duties and responsibilities of this association, which started not from the beginning, but in the mid-2000s, with the establishment of the “Crisis and Accident Prevention Committee.” According to him, the primary responsibilities of the Green Association of Chiya are defined within the framework of the Children’s Committee, Sports Committee, Research and Investigation Committee, and Zrebar Committee, and not forest protection and firefighting. This is while the Natural Resources and Watershed Management Department has no other duty besides the protection of these lands.

This senior member of the Green Association of Chiya finds irony in the fact that the equipment their association has provided over the past 17 years for controlling and extinguishing fires in the forests of Marivan is several times more than all the resources the Natural Resources and Watershed Management Department has prepared and allocated for fire control and extinguishing in the entire Kurdistan province.

He believes that this situation is one of the consequences of presenting inaccurate statistics and distorting facts in the reports of these departments to their higher authorities. When the official reports blatantly underreport the number of fires and the area destroyed compared to what actually happened, it’s obvious that fewer resources would be allocated to them, forcing them to borrow the necessary tools for firefighting from the Chiya association, which alone is supposed to monitor and protect over a hundred hectares of Marivan’s forest lands.

A member and one of the founders of the Zagros Environmentalists Association reveals a truth about the actions of government institutions in firefighting that makes the issue far more complicated than initially hypothesized. He testifies about helicopters that usually arrive at the scene several days after a fire starts. He says that in many cases, these helicopters carry no water to spray on the fires and merely fly over the burning areas as a show. Drawing on his years of experience in fighting fires, he recalls several instances where the movement of helicopters in the direction of the wind has exacerbated the spread of fire. The most recent case he recalls relates to the fire in August of this year, where, according to him, the movement of a helicopter without dropping water in the wind direction resulted in several members of their organization being trapped and surrounded by fire, risking being burned alive if local monitoring and support groups had not arrived in time.

The mention of another tangible experience of a board member of the Green Association of Chiya in dealing with violators further elucidates the issue. He states that some of these groups carry weapons to counter the warnings and prevention efforts of environmental activists. According to him, the security and law enforcement agencies in Kurdistan, which are typically very strict and sensitive about carrying weapons, have shown no reaction after receiving reports of these cases.

Additionally, both interviewed environmental activists confirm that fire extinguishing is only a small part of the process in combating forest fires. More than three-quarters of the work starts after the fires are extinguished, focusing on guarding the areas to guide the fall of half-burnt trees in directions that prevent reignition and watching for individuals who return to the site to restart fires. The senior member of the Green Association of Chiya states that the limited and performative presence of government forces in extinguishing fires accounts for only 25% of the entire fire extinguishing process.

Ammar Goli, a journalist and analyst of political and security issues in Kurdistan, emphasizes the unique characteristics of Marivan’s civil society. He believes that the existence of such a coordinated and free mechanism for forest destruction in this region might be designed by security institutions to create a conflict between ordinary people and the elites and civil society, especially those in Marivan who are particularly focused on environmental issues. The narratives, testimonies, and statements of some residents and environmental activists mentioned in this report support his analysis from various aspects. In a situation where government institutions have left the door open for any kind of violation with their silence, indifference, and tacit approval, they have simultaneously created all the necessary conditions for the hassle-free participation of ordinary citizens in these operations. Civil activists are the only ones attempting to prevent the continuation and spread of these violations, and the logical outcome of such a mechanism will be nothing but pitting civil society activists and elites against ordinary people who are attracted or directed towards forest destruction for various reasons and motivations.

Ammar Goli’s reference to the soil quality of Marivan’s forests for agricultural, orcharding, and livestock purposes prompted us to discuss this matter with Mansour Sohrabi, an ecology and environmental expert, to evaluate his perspective on the vegetation characteristics of Marivan’s forests, their differences with vegetation in other Zagros forest areas, and their impact on soil quality and the fire process. Early maturing and quickly drying vegetation can be considered one of the three elements of the fire triangle (heat, fuel, and oxidizing agent).

Areas where the vegetation growth period has ended are more favorable for starting and spreading fires compared to areas with longer vegetation growth periods. However, soil cannot be considered a fire-causing factor or effective in fires on its own, as it does not form any side of the fire triangle but merely provides a basis for one of its sides, which is fuel. This does not mean denying soil quality as an important motive in the formation of fires. In general, forests, due to higher rainfall percentages and plant cover diversity compared to other lands, have richer soil. Scientifically, the more dense and diverse the vegetation cover, the more intense the biological process within the soil, indicating richer soil. Forest soil is very fertile without the need for chemical fertilizers.

The results of a research article introducing the flora of part of Marivan’s forests, covering over 97,000 hectares, show that there are a total of 113 plant species in 90 genera and 31 different families in this area, indicating high vegetation diversity and consequently rich and fertile soil. However, due to the lack of sufficient data and similar research about other Zagros regions, a scientific comparison of the diversity and quality of vegetation cover of these forests is not possible. Nevertheless, Mansour Sohrabi’s observations and analysis confirm the initial hypothesis about the desirable quality of this forest’s soil for agricultural and orcharding applications.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The findings of this report indicate that the role of government-affiliated human factors in the forest fires around Marivan is significantly greater than initially hypothesized. According to assessments by environmental activists and experts, if government responsible institutions implement their standard deterrent and supervisory mechanisms in Marivan, as they do in other parts of Iran, it is possible to prevent nearly all incidents of forest fires in this region. On this basis, it is recommended to international organizations such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and Conservation International (CI) to persuade Iranian authorities through international mechanisms and working groups to fulfill their responsibilities in protecting the natural resources of Marivan. Additionally, it is advised that residents of villages and residential areas surrounding this district engage in educational programs provided by environmental associations and organizations and avoid any collaboration with violators involved in forest destruction, regardless of their motives.

1 سالانه ۲۱ هزار هکتار از جنگلها و مراتع ایران در آتش میسوزد، دادههای باز ایران، ۲۰ مرداد ۱۴۰۲

4 بیش از سه هزار هکتار عرصه طبیعی در کردستان دچار آتش سوزی شد، ایرنا، ۲۶ مهر ۱۴۰۲

5 هر آنچه درباره جنگلهای کردستان باید بدانید/از تخریب تا اجرای برنامههای احیا، فارس، ۲۵ اسفند ۱۳۹۸

6 “زمینخواری” علت احتمالی جنگلسوزیهای مریوان، دویچهوله، ۱۴ مرداد ۱۴۰۲

8افزایش ۱۳٫۲۵ برابری آتشسوزی جنگل های شهرستان مریوان و سروآباد نسبت به سال قبل، انجمن سبز چیا، ۱۲ خرداد ۱۴۰۰

9آمار آتشسوزی های جنگل های مناطق مریوان و سروآباد در سال ١٣٩٩، انجمن سبز چیا، ۶ فروردین

10 گزارش نقض حقوق طبیعی محیط زیست ایران در دی ماه ۱۳۹۷، کانون دفاع از حقوق بشر در ایران، ۱۲ بهمن ۱۳۹۷

11 تخریب گستردە جنگلهای ضلع شمالی میدان پیشمرگه در شهرستان مریوان، انجمن سبز چیا، ۲۰ مرداد ۱۴۰۱

12 جرم قاچاق چوب، موسسه حقوقی مهر پارسیان، ۱ شهریور ۱۴۰۲

15 ۱۲۰۰ مورد تخریب و تصرفهای شناسایی شدە توسط انجمن سبز چیا در شهرستان مریوان، ۲۶ فروردین ۱۴۰۰

16 انجمن سبز چیا : بیش از ۱۲۰۰ کوره زغالگیری در مریوان فعال است، اقتصاد ۲۴، ۲۸ مرداد ۱۴۰۲

17 راه اندازی خط تولید زغال فشرده در شهر مریوان، گروه مهر صنعت، ۸ اردیبهشت ۱۴۰۰