Kurdish political prisoner Zeynab Jalalian, who is serving her 17th year in Yazd Central Prison, has been transferred to the prison infirmary in recent weeks due to severe pain in her right side. Despite being examined by a general practitioner, she was returned to her ward without receiving specialised medical examinations or definitive treatment.

In recent months, Jalalian has been suffering from severe pain in her right side, which has intensified in recent weeks.

After being transferred to the prison infirmary, a general practitioner only performed a basic examination, and her request to be transferred to external medical facilities for specialised tests was rejected by the Ministry of Intelligence, the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (KHRN) has learned.

Despite suffering from several other conditions, including oral thrush, pterygium, asthma, and kidney and gastrointestinal issues, she continues to be denied access to medical services because of opposition from the Ministry of Intelligence.

Simultaneously, while Jalalian is being deprived of medical services, a team of Ministry of Intelligence interrogators met with her twice in the security office of Yazd Central Prison in June and asked her to sign a “letter of repentance” prepared by the Ministry of Intelligence.

The security officers stated that if she signed the letter, her medical treatment and even her conditional release would be swiftly considered.

Jalalian refused to sign the letter, asserting that access to medical services is her legal right as a prisoner.

Previously, in November 2023, the political prisoner was interrogated by a team from the Ministry of Intelligence while handcuffed and shackled.

She was threatened that unless she expressed remorse, she would be denied all basic prisoner rights, including access to medical services.

Jalalian rejected all the security interrogators’ demands for expressing remorse and considered the interrogation with handcuffs and shackles as a form of torture.

Background

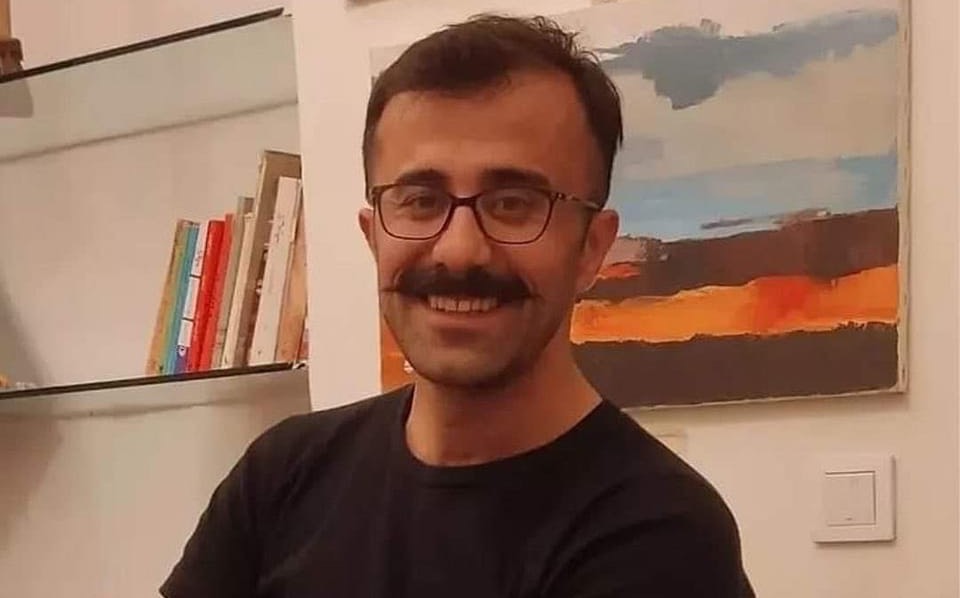

Zeinab Jalalian, born on 6 June 1982, in the border village of Dim Qeshlaq in Maku, West Azerbaijan Province, moved to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq with one of her sisters in 1999.

She initially joined the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and in 2003, after the establishment of the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK), became a member of its women’s branch.

In 2005 and 2006, Jalalian returned to Iran secretly for promotional activities in the provinces of Kermanshah and Kurdistan.

On 26 February 2008, while travelling on an intercity minibus from Kamyaran to Kermanshah, she was arrested by agents of the Ministry of Intelligence at the entrance to the city in front of dozens of passengers.

During the first months of her detention and subsequent imprisonment, Jalalian was subjected to severe physical and psychological torture.

In a trial held on 3 December 2008, nine months after her arrest, she was sentenced to death by Branch One of the Islamic Revolutionary Court in Kermanshah, presided over by Judge Ali Moradi.

The charges against her included “enmity against God” (moharebeh) through “armed action against the Islamic Republic, membership of PJAK, possession and maintenance of military weapons and equipment, and propaganda activities in favour of anti-state groups”.

However, according to the court verdict, Jalalian was unarmed at the time of her arrest, and no military equipment was found on her and the Ministry of Intelligence officials also failed to present any evidence of her involvement in an armed operation.

Nonetheless, the judge issued a death sentence based on the presumption of her potential involvement in armed activities.

According to Jalalian’s lawyers, at all stages of her interrogation she consistently denied any involvement in armed confrontation against the Islamic Republic, stating that her activities were political and in line with the programmes of the women’s branch of PJAK.

In October 2011, coinciding with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s visit to Kermanshah, Jalalian’s sentence was commuted from execution to life imprisonment through the “Leader’s Amnesty”, based on the recommendation of the Amnesty and Clemency Commission of the provincial judiciary.

Her lawyer, Amir Salar Davoudi, who is currently imprisoned for his human rights activities, had previously emphasised in an interview that the request for clemency for Jalalian was not initiated by her or her legal representatives, but was directly proposed by the Amnesty and Clemency Commission of Kermanshah Province.

Explaining the cancellation of Jalalian’s death sentence as a result of this clemency, he said: “The reason for this proposal by the Kermanshah Amnesty and Clemency Commission was that the provincial office of the Ministry of Intelligence withdrew its initial report about Zeynab Jalalian being armed and using weapons and admitted its mistake. This report is in the case file and has a reference number. But the question is why the Ministry of Intelligence’s report, which was previously the basis for the conviction, is now only the basis for clemency from the death penalty. In fact, the public prosecutor could have asked for a retrial in light of this report.”

Davoudi had also previously pointed out that under the new Islamic Penal Code passed in 2013, Jalalian’s sentence could not exceed 15 years, and that continuing her imprisonment beyond that period would be against the law. The revised law removes the charge of “enmity against God” (moharebeh) for political accusations and instead considers equivalent charges.

He said: “The Islamic Penal Code was amended in 2013 regarding charges related to armed confrontation against the Islamic Republic or membership of armed groups. Essentially, the charge of ‘enmity against God’ for which Zeynab had been sentenced was removed in relation to political accusations and an equivalent charge was considered. According to this law, if an individual is arrested without a weapon and detained until the central command of the group is intact, they will be sentenced to 10 to 15 years in prison. This law applies not only to Zeynab, but also to many other convicted individuals. If it had been applied, Zeynab’s sentence would have been reduced to third-degree punitive imprisonment and she would have been released by now.”

The lawyer had previously said that with the new law in place, the prosecution could have asked for the case to be reviewed. Also, the Supreme Court has not responded to the formal request by Jalalian’s lawyers to review the case.

Jalalian, who has been held in Yazd prison for the past four years, over 1,300 kilometers away from her family’s residence, has developed various illnesses during her lengthy and harsh detention, including pterygium, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), impaired vision, dental infections, kidney and gastrointestinal problems, COVID-19, and asthma.

Despite her need for medical treatment outside prison, authorities have refused to transfer her to a hospital under orders from security agencies.

In June 2023, the KHRN had reported that on 6 June, following a celebration by some women prisoners in Yazd Central Prison for Jalalian’s 41st birthday, the prison security authorities summoned a group of these prisoners and threatened them with legal action.

On 9 November 2020, she was transferred from Khoy Prison, the closest prison to her family residing in Maku, to Yazd Central Prison without any legal justification.

About six months before her transfer, on 29 April 2020, security forces transferred her to Qarchak prison in Varamin, northern Iran.

Two months later, she was transferred to Kerman Prison and held in solitary confinement for a period of time while she was infected with COVID-19 and was on a hunger strike, demanding her return to Khoy Prison.

On 22 September 2022, security forces moved the political prisoner from Kerman Prison to Kermanshah Prison.

The authorities at Kermanshah Women’s Prison had initially refused to admit her to the prison because of the injuries she had sustained to her wrists and feet after being dragged to the ground in handcuffs and shackles by security forces.

Later, in Yazd prison, Jalalian was infected with COVID-19 for the second time. Despite her deteriorating physical condition, she was held in a room for addicted prisoners, with very poor hygienic conditions and no access to proper medical care.

These illnesses, which have been confirmed by the prison doctor, along with her pre-existing conditions such as kidney and gastrointestinal issues, pterygium, foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), impaired vision, and dental infections, all of which developed during her imprisonment due to repeated torture and harsh prison conditions, have severely deteriorated Jalalian’s physical health.

In recent years, due to transfers between various prisons and the distance between Yazd and her family’s home in Maku, along with security restrictions, Jalalian has been unable to meet her family.

Agents of the Ministry of Intelligence in Yazd Prison warned the political prisoner that if any information about her condition was leaked to the media by her and her family, it would increase the pressure on her and lead to her transfer to another prison.

In March 2022, security forces arrested Jalalian’s parents and three brothers in Maku after a video was released of her mother, Gozal Hajizadeh, talking about her daughter’s condition in prison.

Although the family members were released 24 hours later after Hajizadeh fell unconscious in custody, the Intelligence Ministry warned them not to disseminate information or speak to human rights organisations or the media about Jalalian’s condition.

The security forces also asked the family to speak in a video interview against the activities of the political prisoner and Kurdish opposition parties, which they strongly refused to do.

In 2016, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention officially requested the Islamic Republic of Iran to immediately release Jalalian and take all necessary measures to compensate her without delay in accordance with international standards. The group described Jalalian’s deprivation of liberty as arbitrary and contrary to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, obligating Iran to prosecute those responsible for violating this Kurdish political activist’s rights.